[ad_1]

This is the story of the economic shockwave currently running through this country – along supply chains, into the prices of the materials and services we use every day.

It is the story of how an energy crisis very quickly turns into an everything price rise.

It’s hard to know where to begin, so let’s begin at the very beginning of one of those supply chains.

Let’s begin with one of the most basic materials of all: salt. Most of Britain’s salt comes out of the ground in Cheshire, from a slab of halite – rock salt – hundreds of metres beneath the ground.

Water is pumped down, along with compressed air, and what comes back up is brine – water with a salt concentrate of just over 30%.

So far this hasn’t taken much in the way of extra energy costs, but just wait. Because having been extracted, that brine is then pumped over to British Salt’s main plant in Middlewich. Here, it is purified and treated in giant vats with lime and other substances which remove impurities like magnesium and sulphates.

Then, that pure brine is pumped into a massive evaporation plant, where it is heated up in vast vessels, not once or twice but, six times. The vessels are highly pressurised and very hot.

By the time the salt has been through them, it has lost most of its water and has the texture of wet sand.

Then it goes through yet another drying process which removes the final three per cent of moisture. Finally, you have the finished product: pure vacuum dried salt, or as we call it, table salt.

It’s worth noting all these stages not merely because it might comes a surprise that most of the salt we consume comes to you this way, but also because it is very energy intensive.

By far the biggest cost for British Salt is energy, to power the gigantic gas-fired boilers they have which provide heat and electricity to the plant.

‘We don’t have a magic wand’

In the long run it’s possible that we might come up with electric boilers capable of doing what the ones here at British Salt do, but for the time being, the most efficient way to provide both power and (more importantly) heat to the evaporation vessels is by burning natural gas.

And, as everyone knows, the price of natural gas has gone up enormously in recent months. And while day-ahead prices have dropped sharply in recent weeks, the reality is that most big manufacturers have hedged their energy prices.

This means they are somewhat insulated against energy prices. But only somewhat.

For British Salt, gas prices are comfortably the biggest cost.

According to Joe Evans, who runs the plant: “The evaporation process relies on the steam input that’s derived from natural gas in the boiler. Typically it demands around 45 tonnes an hour of steam in order to reduce that moisture content.”

So that’s salt; and understanding all of that helps explain why the inflation category that includes salt is up by 13% in the past year alone.

But according to Martin Ashcroft, managing director of Tata Chemicals Europe, which owns British Salt, we’ve only really seen the beginning of it. Because those energy costs are still coursing through their balance sheet.

“We don’t have a magic wand to say: ‘let’s use less energy’,” he says. “The only way to use less energy is to produce less. And obviously, that then means there isn’t the sufficient material to feed into the UK economy.”

You literally can’t live without salt. The body is in part an electrochemical system which relies on salt to function.

So the fact that salt is rising in price is of significance. However, it is just one part of a deeper issue, which is that the energy crisis is fuelling a food crisis.

One of the most disquieting indirect problems to derive from the war in Ukraine is the consequences for global food supplies.

It’s helpful to divide the coming food crisis into two parts.

The first is the direct impact of the shutdown of trade coming from Russia and Ukraine. Clearly, we will be receiving much less wheat, vegetable oils and fertilisers from these countries (and Belarus) in the coming months, due to sanctions and war destruction.

This is likely to trigger food shortages and potentially social unrest in many parts of the world – especially sub-Saharan Africa. This is a humanitarian crisis in the making.

However, there is also a more subtle chain reaction at play here, which comes back to natural gas prices.

‘Preposterous’

To see it at play, it helps to visit a greenhouse where many of the fruits and vegetables we eat are grown. There are many of these in Britain, though the world leader for this trade is the Netherlands, one of the world’s biggest food exporters, with hundreds of square kilometres devoted to indoor horticulture and agriculture.

I visited one of these complexes of greenhouses in the Lea Valley just outside London.

At Valley Grown Nurseries they are growing peppers and cherry tomatoes. Nof Nicastro picks me a tomato as we walk down the aisle. The tomato is sweet and delicious, the greenhouse is warm and there are bees buzzing everywhere (they are there to pollinate the tomatoes). But the warmth comes at a cost.

The greenhouse is kept at a constant temperature by an enormous gas-fired boiler which sits just next to the car park.

Not only does the boiler provide heat, it also helps the growing process in another unexpected way, for carbon dioxide from the chimney is filtered out and pumped into the greenhouse.

The air in there is kept at around 700-800 parts per million of CO2 (as opposed to 350-400ppm outside). Plants consume CO2 during photosynthesis, so the more there is in the air, the faster the tomatoes grow.

This so-called CO2 revolution transformed the industry back in the ’90s, but it makes growers even more reliant on gas.

And with natural gas prices so high, that has caused an enormous dent in their margins.

Up until this year, the idea that any of the growers in the Lea Valley would leave their greenhouses empty would have seemed preposterous, but this year half of them have been left fallow.

Nof tells me this may well have been the wise decision; it may well be that his decision to grow this year was the wrong one, given how rapidly his costs are stacking up.

Turn the boiler down a touch and the tomatoes face fungal infections and other diseases. Stop pumping as much CO2 in and they droop and don’t grow.

And it’s not just natural gas itself pushing up prices. The price of fertiliser is also rocketing. Why? Because fertiliser is itself a kind of fossil fuel: the Haber Bosch process of nitrogen synthesis uses natural gas as a feedstock and energy source.

Perhaps you are beginning to see the issue here. It is all very well saying we need to use less gas, but that somewhat elides the fact that so many processes and products in the UK (and for that matter elsewhere) are produced using finely tuned systems which have natural gas at their core.

Back in Cheshire, the salt that comes out of the ground is destined for far more uses than just table salt. For Tata Chemicals also turns brine into soda ash – sodium carbonate.

Soda ash is one of the fundamental building blocks in manufacturing: it is used in glass production as a “flux”, a chemical which allows you to melt glass at reasonable temperatures, it is a critical component of soaps and detergents. It is, in short, very, very important.

But turning salt into soda ash is another one of those energy intensive processes. So energy intensive that Tata Chemicals actually have their own combined heat and power plant at Winnington. This power station uses natural gas to produce steam and electricity, which then powers their soda ash plant (and the one that turns soda ash into sodium bicarbonate).

Biggest increases may be yet to come

In an echo of what happens in the greenhouses at the Lea Valley, they also capture the CO2 coming out of the chimney and use it in their chemical processes (you need it when you’re making soda ash and sodium bicarbonate). It is yet another finely-tuned production cycle where nearly every joule of energy is captured and turned into the products we use every day.

Here, as in those greenhouses, the multiplying energy costs are already weighing on things. Tata Chemicals have put up prices a few times but the biggest increases may be yet to come.

Tata, like most manufacturers, has hedged its power prices for some months, but as those hedges expire, so their costs climb even higher. And as they climb higher so their prices rise higher. And as those prices rise higher, so do the costs of everyone further down the chain who use their materials in their processes.

Not far away in Wigan, just outside town in a big industrial estate you will find Nippon Electric Glass. Here they make fibreglass, an extraordinary material made of hair-thin strands of glass, woven together into a material which is considerably stronger, by weight, than steel.

Fibreglass is one of those materials no one spends much time thinking about but without which the world as we know it would be very different indeed.

Most strong plastic materials are made of a plastic and fibreglass mix: the dashboard of your car, the bumper. Fibreglass is what gives it strength; it is one of the basic materials we build our world out of.

It is also, by the way, the main structural material for the blades of wind turbines. That’s right, wind turbines are made out of glass!

You’ll probably already have guessed what’s coming next.

Turning sand into glass – even with a flux like soda ash – involves heating it up to 1,600 degrees in an enormous furnace. You fire natural gas mixed with compressed air into this cauldron and gradually, as it travels metre by metre down the furnace, the mixture of sand, soda ash, limestone and other materials begins to melt.

By the end of the furnace it is a bubbling, white-hot liquid. That liquid then drops through tiny holes and comes out in the form of tiny strands.

Costs will go up dramatically

According to Steve Keeton of Nippon Electric Glass, his costs are up about 50% so far. That isn’t just the cost of gas. In fact, he hedged his gas costs last year meaning they’re far more reasonable than anything you can find on the market these days. But his raw materials: stuff like sand and, yes, soda ash, are far more expensive.

So far, he has had to raise his prices about 25-30%. A lot, but not as much as some other manufacturers. But here’s the thing. Next March his energy hedges will expire. At that point, those costs will go up dramatically – perhaps another 40-50%.

Squint a bit and you can see a lot of inflation coming down the pipeline. Some of it embodied in the basic building blocks that go into loads of other products – stuff like salt and soda ash – some of it has not even crystallised yet because producers are still temporarily protected by hedges.

Now let’s take a step back from these supply chains and ponder what most economists are now forecasting for inflation.

They believe that after a sharp increase this year, inflation will drop down next year to six per cent or so, and it’ll be back down to two per cent in 2024. That might well eventuate.

Gas prices might well fall sharply and stay low in the coming months. But looking down these pipelines, 2% inflation in 2024 does not seem like a dead cert.

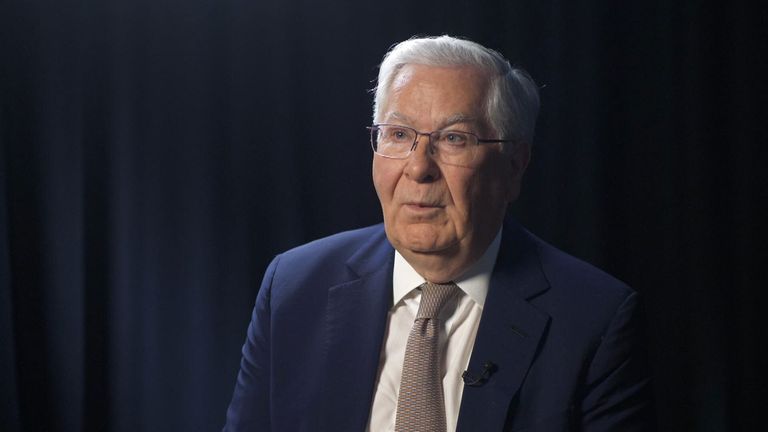

And Mervyn King, the former Bank of England governor, certainly doesn’t think so. He calls this the King Canute paradox.

He says: “The Bank of England and I think all major central banks have fallen prey to the same misconception that just by stating an inflation target, you build into your models and your forecasts the assumption that inflation in the long run will always come down to 2%.

“I think that’s a real stretch.”

Indeed, he reckons that part of the explanation for high inflation right now is the extra money central banks like the Bank of England printed after the onset of COVID-19.

“They shouldn’t have been printing the extra money,” he says. “What governments were doing was enough to deal with the consequences of COVID.

“They’re now worried about inflation, when they weren’t before. [But] it’s not all the result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This was foreseeable, because there was a mistaken diagnosis of what needed to be done with the pandemic.”

However, the idea that central banks are primarily to blame for the cost of living crisis is a contentious one (especially coming from someone who used to occupy one of these roles).

A harder shock

Others argue this was in part a consequence of the dramatic economic yo-yoing of the world during the pandemic.

Still others suggest that it stems from a dramatic dearth of investment in primary energy in recent years – something which meant the minute the world demanded more energy, the system simply couldn’t supply it.

According to Helen Thompson, professor of political economy at the University of Cambridge, there were deeper and wider root causes.

“I think in some ways this is a harder shock than in the 1970s,” she says.

“If we just concentrate on oil for a moment, which was the centre of the energy shocks in ’70s (gas was less important as an energy source), the fundamental thing that was going on was that the Arab states were using oil as a geopolitical weapon.

“But I don’t think that there was any deep underlying issue with the supply of oil through the 1970s. I think that what we can see now is actually that it’s quite difficult for all the world’s oil producers put together to meet the demand for oil when the world economy is growing beyond a moderate level.

“And that puts us into a difficult position – a harder position in the ’70s.”

The other problem is one you’ll already have absorbed by now: there really is no escaping from energy costs. They come at you from every part of the supply chain. And while the examples above might be mostly from the manufacturing sector, other parts of the economy are clearly affected as well.

Part of the reason why the price of haircuts is up by 5.5% in the past year is that the cost of materials (such as hair products which are in part made from chemicals such as those produced by Tata Chemicals) is up.

So too, is the cost of the electricity powering hairdryers and gas heating their hot water.

As Thompson says, “energy is actually central to economic life. In one sense economic activities is simply the deployment of energy to try to produce things. So when a shock happens in the energy sphere, then it necessarily has to go through the whole economy”.

As far as Lord King is concerned, the fact this economic shock is being delivered via energy makes it especially painful for the UK.

‘There’s nothing we can do’

“The real issue here is that we don’t produce all the energy ourselves,” he says. “So we have to import quite a lot. And that means that when energy prices go up, it’s a bit like the rest of the world imposing a tax on us as a country. So as a country, we’re worse off.

“And there’s nothing we can do about that.

“That makes it much, much harder to provide help and support for those who are hardest hit, because it’s going to double down on the hit on people on average incomes or better off incomes, and there just aren’t enough very rich people to tap to make that transfer to keep the rest of us from suffering too much.

“Everyone basically takes a hit when energy prices go up.”

The deeper you delve into the businesses which make our world tick, the clearer this logic seems.

A decade and a bit ago the world faced an economic crisis when the system of financial wiring that connected us malfunctioned.

Today the crisis is bound up in the wiring itself – in the pipes and cables we rely on to provide our most basic needs.

Shelter, food, heat: the very bottom of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

This is why this crisis is so serious. It is an economic shockwave we cannot help but feel.

[ad_2]