[ad_1]

By many measures General Paul Nakasone, the man who heads both US Cyber Command and the National Security Agency, is the world’s most powerful decision-maker when it comes to setting the rules of international cyber conflict.

Some might question whether those rules matter. Since 2010 groups of government experts at the United Nations have agreed several non-binding voluntary norms about cyber conflict, but these have not prevented a number of extremely impactful state-sponsored incidents.

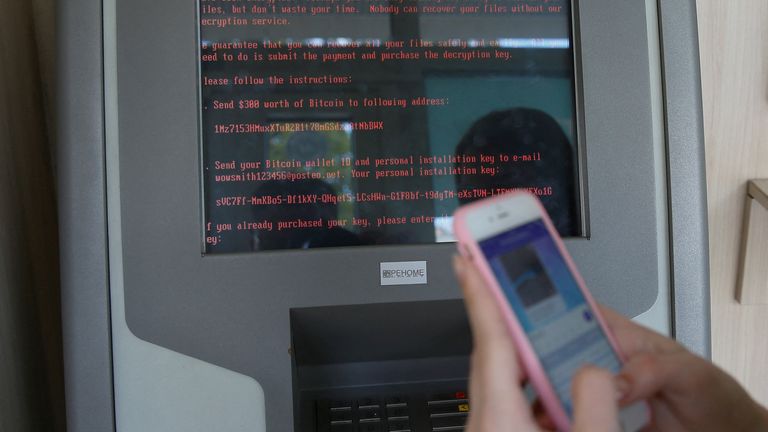

The Microsoft Exchange breaches of last year and the wildfire catastrophe of the NotPetya attack against Ukraine in 2017 were allegedly even committed by States who have publicly said they were in favour of these agreements.

Yet work on setting the rules continues among a multilateral coalition of democracies – many of them NATO members, with some set to join the alliance in the near future – alongside legal scholars and academics.

Representatives meet around events such as CyCon, hosted by NATO’s Co-operative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn, Estonia, to discuss what is right and wrong when conducting or defending against computer network attacks.

General Nakasone, who spoke exclusively to Sky News directly after delivering the opening keynote at the conference – and following a two-day forum with cyber commanders from 34 other nations – said the discussions about “how do we operate within this domain collectively” are fundamentally multilateral.

These are “unique partnerships, different partnerships,” he told Sky News, something which he said was valuable because “being able to operate with a series of like-minded nations… enhances the security of our collective actions”.

Autocracies get and don’t give

Even before taking office, when being grilled by US senators about his potential appointment, the general has stressed the need to persistently engage with adversaries both offensively and defensively, working not just on the behalf of the US but for its partners as well – most recently including Ukraine.

“Our ability to have a series of partners globally provides us a presence in being able to address threats to our collective security. This is what is attractive to us in a trans-border world in which we are able to find like-minded nations that do want to operate with us for a free and open internet. This is where partnerships are really important,” he told Sky News.

“I think if you were to go to talk to any of our partners that work with us, either US Cyber Command and the National Security Agency, one of the things that those nations would tell you is we get and we give, this is not a client relationship. This is a partnership upon which both nations get value.”

Autocracies “get and don’t give – it’s as simple as I could outline it” he said, while in comparison those partnering with US Cyber Command would in turn receive “information, intelligence, capabilities, capacity, planning, [and] support”.

The “brutal unjust invasion of Ukraine, by Russia” as he described it, offered a great example of how “democratic nations establish rich, robust partnerships” while “autocratic nations ally with clients” he said, adding in his CyCon keynote: “The difference is marked, recognisable, and an asset to ourselves and our allies and partners.”

Speaking to Sky News directly after this speech, he said: “One of the things that I certainly have learned is these partnerships are really powerful. You look at and you see how the Ukrainians have been able to maintain an open internet during this time of crisis and conflict, [and that is] really a great tribute to them.”

Unlike in classical models of shooting wars where armed forces compete against each other to control territory, conflicts that have a cyber dimension involve operating in computer networks that are controlled by private companies – and these companies have a significant ability to shape the outcome of those operations.

Control over physical internet infrastructure is a mid-way point. Ukraine’s State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection has detailed its own work and that of repair technicians from companies like Kyivstar to ensure Ukrainians, even under occupation, have access to information that isn’t controlled by Russia.

“The enemies’ objective is obvious – to strip our people of any access to true information, making Russian propaganda the only available information source, to disrupt their contacts with their families thus escalating panic and blaming the Ukrainian government for leaving their people behind,” the service has stated.

In a conversation at Cyber UK in May, Paul Chichester, the director of operations at the National Cyber Security Centre, described defending Ukraine’s networks as the “primary mission” for a number of global private sector companies in the same way that it had been the primary mission for cyber security experts in the British government and among allies.

General Nakasone described Cyber Command’s hunt forward operations – when defensive experts are deployed in a country to hunt for attackers on that country’s computer networks – as an example of the benefits of partnership.

He said: “This ability for us to work at the behest of a foreign government to go and hunt with them on their networks, then releasing the information. We have released over 90 different malware samples to a series of private sector cybersecurity firms.

“What does that do? It provides inoculation for all of us that operate in the domain. And I think that’s an example of where this public-private partnership so important.”

Hunt forward exercises are “always transparent and collaborative – we share the information, not only with the partners, but also release it to the public too,” he added – stressing a faith in shared knowledge that stands in stark contrast to the alleged challenges that Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has faced in getting ground truth from his military and intelligence agencies about the war.

Russia has ‘clearly performed below expectations’

The Russian armed forces have “clearly, clearly performed below expectations” during their invasion of Ukraine, he said: “We’ve seen this in terms of their initial focus on Kyiv, their inability to synchronise their operations, their retreat from what was their central focus in being able to take the capital city of Ukraine.”

But he cautioned: “There is still a very, very broad and unjust war that’s ongoing right now.”

Whether the expectations among Ukraine’s allies should have been different is “a question that we certainly ask ourselves as we go forward, and we will be looking at that… [But] we also have to understand that our adversaries also learn, and so this is still ongoing.”

He said his crystal ball wasn’t appropriate to predict how the conflict in Ukraine would end: “As our secretary of defence has indicated, I think, very appropriately, as has our director of national intelligence, this is a conflict that may go on for quite some time.”

Asked whether the conflict in Ukraine had shown that cyber operations were incapable of – by themselves – achieving strategic military objectives, he said: “I think that’s too binary in terms of, you know, what we’ve seen over the period of, you know, a little more than 90 days. I think it’s too early.

“I think that cyber has an important role in any type of future crisis or conflict. And that’s determined by, you know, the crisis, the conflict and what it’s also used with, I think that’s a big piece.”

General Nakasone added: “One of the things that we certainly learned is the importance that the Ukrainians have placed on having a resilient network.

“Of all that’s said in terms of what’s gone on in this conflict, one of the things that I think is sometimes missed is that the Ukrainians have maintained their internet and being able to communicate, and this is great tribute to them.”

Offensive cyber operations

In the first part of the Sky News interview with General Nakasone he confirmed that US military hackers have conducted offensive cyber operations in support of Ukraine, although he did not detail what these operations were.

For the US military “offensive cyber operations” as a term can encompass a range of activities – some potentially more escalatory than others – although the four-star general stressed that US Cyber Command always acted within the law of armed conflict.

Responding to a question about whether the US had conducted offensive operations in support of Ukraine, he said: “We’ve conducted a series of operations across the full spectrum; offensive, defensive, [and] information operations.”

He explained why these operations were legal in comparison to those the US and allies had attributed to Russia: “Within our system, just as within our fellow democratic nations, we operate with a clear civilian control of the military. Secondly, we do everything that is obviously within the law of armed conflict. Third, you know, this is a policy matter that our government works in terms of our left and right boundaries.

“My job, and all of this, is to provide a series of options to the secretary of defence and the president. And so that’s what I do. And that in the policy piece, is obviously handled by those within our Department of Defence,” he explained.

Separately during the interview General Nakasone cited a range of serious cyber attacks last year, from the Microsoft Exchange breaches to the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack and another on Kaseya, stating: “We’re much better prepared [today] through a series of executive orders and our continued partnerships with a number of different players. It’s different in 2022 than it was in 202, and I think the vigilance is a significant difference.”

He told Sky News how impactful these operations could be: “If you’re an adversary, and you’ve just spent a lot of money on a tool, and you’re hoping to utilise it readily in a number of different intrusions, suddenly it’s outed and it’s now been signatured across a broad range of networks, and suddenly you’ve lost your ability to do that.”

Following our interview White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre was asked specifically about the general’s comments and whether US offensive cyber operations risked an escalating Russian response.

She stated: “We don’t negotiate our security assistance packages to Ukraine. The Kremlin has not been pleased by the amount of security assistance we’ve been providing to Ukraine since far before this most recent phase of conflict began.

“But we are doing exactly what the president said he would do – and what he told President Putin directly we would do if he attacked Ukraine back in December – which is provide security assistance to the Ukrainians that is above and beyond what we are already providing,” she added.

Responding to whether the offensive cyber operations were contrary to the US position of avoiding direct engagement with Russia, Ms Jean-Pierre said: “We don’t see it as such. We have talked about this before. We’ve had our cyber experts here at the podium lay out what our plan is. That has not changed. So the answer is, just simply, no.”

Analysing these comments Professor Michael Schmitt at the University of Reading – writing as a scholar at the US Military Academy at West Point – noted that legally the US could conduct offensive cyber operations in support of Ukraine’s right of self-defence so long as they were requested by Ukraine, although he recognised it was impossible to assess the operations fully without knowing what actions General Nakasone was referring to.

In a statement on Monday 6 June, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused “Ukraine, with the help of the United States” of “carrying out cyber attacks on the critical infrastructure of the Russian Federation” and said: “If the provocations continue, the answer will be firm and decisive.”

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to a Sky News enquiry about what these attacks were, nor explain what was meant by a “firm and decisive” response.

Speaking to journalists this week Victor Zhora, deputy head of Ukraine’s State Special Communications Service, said that Ukraine does not conduct offensive cyber operations but does conduct defensive ones together with its partners.

In his analysis, Professor Schmitt noted a vote at the UN in which of the body’s 193 members “141 States voted for a General Assembly resolution condemning the Russian actions and demanding immediate and unconditional withdrawal. Thirty-five abstained (likely for political, not legal reasons), while only five (Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Russia, and Syria) voted against the resolution”.

“As I mentioned previously, countries want to work with us,” said General Nakasone. “They want to work with us because we both give, and we both build a partnership that means something.”

[ad_2]